Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Features

Features > Images Of Doi Mae Salong

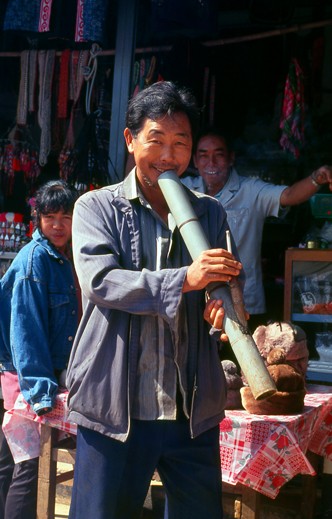

Images Of Doi Mae Salong

A vision of pristine hills, long ago, straddling an unmarked and unobserved frontier between states as yet unformed. Unpopulated save by birds and beasts, the only human visitors are wandering hunters, mystics and anchorites, refugees from justice – or from oppression. A Southeast Asian Shangri-la without name and beyond knowledge, silently awaiting discovery and settlement.

Unknown to the hills, in the surrounding plains humanity draws nearer. The inhabitants of China, the Middle Kingdom, push south. Denizens of Burma, The Golden Land, drive east. To the south an old people, supple and resilient as bamboo, create a rich new state in a bountiful region with fish in the waters and rice in the fields... The foundations of an independent Siamese polity are being established.

Six centuries pass. In the fertile lowlands, areas suitable for wet rice cultivation, Tai-speaking peoples – Shan, Lao and Northern Thai – come to dominate. Yet still the hills remain inviolate, feared and shunned by paddy farmers; the abode of bandits, tigers and spirits in tales to frighten and delight their children. Then - about 100 years ago – new types of men appear. Men with business in the hills.

First, fleeing failed rebellion and seeking new opportunities, come the Yunnanese. Mainly Muslims from the west of the province, these sturdy traders have long dominated the rugged and inaccessible trade routes of the Sino-Burmese borderlands, dealing in goods as diverse as cotton and preserved fruit, repeating rifles and opium. Now they seek new and secure bases for their trading operations – out of reach of the vengeful Ch'ing authorities, yet not so far south as to excite the interest and attention of the Chakri Dynasty in Bangkok.

Second, pushed south and eastwards by the pressure of expanding sedentary populations – Chinese, Burmese and Shan – come the minority hill peoples. These wanderers – Lisu, Lahu, and finally Akha, the latter from the fringes of distant Tibet – seek refuge in isolation on land as yet untilled, in the farthest foothills of the Himalayan chain.

Third, and last, and most surprising, come the Europeans. By some strange quirk of fate they are, predominantly, Celtic. The British – long-time rulers of India and recent conquerors of Burma – send a Scotsman to subdue and survey their newest acquisition, the distant Shan States. The Siamese authorities respond, wisely employing the traditional Chinese tactic of "using barbarians to control barbarians", by sending an Irishman to survey and lay claim to parts of the same region*. As a result watersheds are mapped, ranges are named, and boundaries are agreed. Consequently, one remote and sparsely inhabited region – Doi Mae Salong, or "Salong Stream Mountain" – is deemed to belong to Siam and ratified by international agreement.

Again, time passes. In 1939 Siam becomes Thailand. Ten years later the Chinese Civil War ends in victory for Mao Tse-tung and the Communist Party. The Peoples Liberation Army enters Yunnan, driving before it the defeated Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek, known in Chinese as the Kuomintang – or KMT for short. Most KMT armies surrender. Others seek refuge in the Nationalist redoubt of Taiwan. In distant Yunnan three Nationalist armies, including the tenacious 93rd Division of General Tuan Shih-wen, refuse to surrender and withdraw across the Burmese frontier, vowing to continue the struggle against communism.

In 1956, after seven years in Burma and three abortive invasions of their Chinese homeland, the KMT are forced out by a coalition of the Tatmawdaw – the ragtag Burmese military – and their real enemy, the communist PLA. Some choose to fly to a new life in Nationalist Taiwan. Others withdraw across a second frontier, to Thailand, where the staunchly anti-communist governments of Thanom Kittikachorn, and later Sarit Thanarat, extend a warm – if discreet – welcome.

A further twenty years pass. The communist insurgents of the PLAT – the Peoples Liberation Army of Thailand – are demoralised and defeated, in no small measure due to the efforts of the KMT "Ghost Soldiers" stationed at Doi Mae Salong. The Thai authorities are grateful – but have no further need for "Chinese special forces" on Thai soil. Doi Mae Salong's name is officially changed to Santhikiri, or "Hill of Peace". Paved roads are built. Thai schools supplant the Chinese, and portraits of King Rama IX replace those of President Chiang Kai-shek. Poppies disappear from the surrounding hills, whilst new crops – tea, coffee, corn and fruit orchards – appear.

And yet, despite these changes, Doi Mae Salong remains uniquely Chinese, a replica of a Yunnanese village transplanted to the hills of northern Thailand. In consequence, tourists arrive – Thai, European, and especially Chinese from Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Hotels and restaurants are built. Resorts appear. Business – legitimate business – booms.

By 1994 the hills around Doi Mae Salong remain distant and still – at least in the cold mists and dew of the early Southeast Asian dawn. Yet the tomb of Tuan Shih-wen, staunch anti-communist and KMT die-hard, looks down from its perch atop the peak on a thriving capitalist enclave.

* The late 19th century British survey of the Shan States was completed by the Scotsman, Sir George Scott, whilst the contemporaneous survey of the Lao-Shan hills was carried out by an Irishman, McCarthy, in the service of the Royal Thai Government.

Text by Andrew Forbes; pictures by David Henley & Pictures From History – © CPA Media