Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Archives

Archives > BURMA / MYANMAR > Tazaungmon

Tazaungmon

Under A Shan Moon

The full moon in November is a magical time for Thai Buddhists everywhere. As that luminous orb rises against the darkening night, countless rockets fill the sky and millions of krathong — delicate yet elaborate floats bearing offerings of incense, candles, small coins and sweet-smelling flowers — fill the rivers and canals of this ancient country. The floats are to honour Mae Khongkha, the river goddess, and to acknowledge the bounty of her annual inundation's effect across the fertile floodplains of the kingdom. Krathong also bear away the sins of the offerer, and — should the floats of lovers drift away, side-by-side, into the night — give promise of a long and happy marriage. It is a time of joy and celebration, filling the entire nation with a spirit of renewal, perhaps the loveliest of all Thailand's traditional festivals.

Yet Loy Krathong does not belong to Thailand alone. Wherever Tai-speaking peoples live, from the rice fields of China's Sipsongpanna to the Kampong Syam of Kelantan, those amongst them who are Buddhist will honour Mae Khongkha whilst making merit, in the hope of a better future and atoning for past misdeeds.

Thus all Tais celebrate - but not all in the same way, or at the same time. There are regional variants and differing ways of sloughing off sin. Laos, for example, is rich in rivers, so water-borne krathong renew the individual as in Thailand, though a month earlier, at October full moon, in deference to the old Lan Na calendar. In Chiang Mai there are waterways aplenty, but the tradition has been marked by the proximity of Burma, and khom loy, or hot-air filled balloons trailing magnesium flares and firecrackers are used as an aerial adjunct to the floating away of sins. A few years ago so many were released that more than three thousand gathered in an incandescent cloud over the city, forcing the temporary closure of Chiang Mai International Airport.

Still more spectacular is the custom in Burma's neighbouring Shan State. Here, where the great festival is called Tazaungmon, a weaving ceremony is held. Young Tai maidens sit out under the full moon in the temple grounds, engaged in weaving competitions to produce new robes for the monks. In the early morning, as the sun rises over the Shan hills, the newly-finished saffron robes are presented to the sangha in part of a great merit-making ceremony designed to smooth the path of life ahead. It is a gentle and evocative custom, redolent of all that is tranquil in Theravada Buddhism.

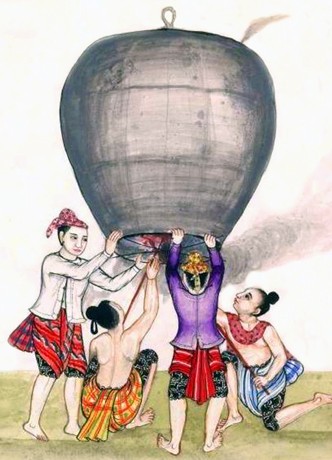

Meanwhile the Shan men, and not a few Shan women as well, have been involved in something far more spectacular, impressive, and often remarkably destructive. For in Shan State, at Tazaungmon, sins are floated away in giant hot-air balloons, rivers being relatively scarce in this great upland region. These are not the modest, if spectacular khom loy of Chiang Mai, but great leviathans two and three stories high, fired by coal braziers and dripping with thousands of candles.

I first learned of this antique custom in the writings of Shway Yoe, otherwise known as Sir George Scott or "Scott of the Shan Hills", the first colonial administrator of this remote region following the British take-over in 1886. On a rainy day at King's College, Cambridge, I mentioned it to Sao Saimöng Mangrai, the great Shan historian now sadly deceased, and was rewarded with an invitation to visit him, at Tazaungmon, in Taunggyi, the capital of Shan State.

The journey from Rangoon to Taunggyi is hot, dusty and uncomfortable as far as the uninspiring railway junction of Thazi. The bucking, juddering nightmare that is the Rangoon-Mandalay "Express" gets into town at about 5.00AM. It's probably best to await the dawn over a cup of sweet, milky Indian tea at a roadside stall before attempting to negotiate a ride in a truck to distant Taunggyi. Once out of town and on the road east things start to improve rapidly. The road rises swiftly from the arid plains, switch-backing into the cool green heights of the Shan Hills. Taunggyi — which means "Big Mountain" in Burmese — is about seven hours distant, and the temperature falls noticeably as the elevation increases.

Beyond Kalaw both the scenery and the ethnic make-up change drastically. Pine trees first outnumber, then replace, the sugar palm. Tai-speaking Shan outnumber - but do not replace - the ruling Burman bureaucracy. In practical terms, this means that Burmese lunggyi sarongs give way to baggy Shan trousers, whilst Shan turbans and broad-bladed dah swords are much in evidence. Fittingly, Taunggyi is perched on top of a great, mist-shrouded cliff. A town of Shans and Burmans, ethnic minorities such as the Pa-o, Karenni, Karen and Kachin are much in evidence at the markets, as are Yunnanese Chinese.

Sao Saimöng, known locally as sao lung or "royal uncle", was waiting to greet me at his Tudor-style mansion in the lee of the great hill. A scion of the royal house of Kengtung, he had been brought up in the sawbwa's palace, fought as an intelligence officer with the British during World War II, and been arrested by the Burmese military authorities as a "suspected separatist" following the coup of 1962. I only learned of this latter experience when questioning him about the home-made solar water heater constructed of criss-crossed lead piping on the roof of his house. "For seven years at Insein [Rangoon's central prison] I dreamed of cool water", he explained. "It was a vain hope. Tap water reached us after a long journey across the baking plain, and was almost too hot to drink. When I got back to my beloved Shan Hills, I thought I should put that experience to some positive use. Now I bathe in warm water in my old age".

That evening Sao Saimöng took me to see the fire balloons. They were launched, by competing teams representing the various wards of Taunggyi, from the football ground opposite the San Pya Guest House in the centre of town. Wrapped tightly against the chill of the night — Taunggyi becomes seriously cold in November — groups of young men struggled to erect great mulberry paper balloons. First, one would be inflated, using a hot coal brazier in a suspended woven bamboo basket. Then, as the great dome filled with hot air and floated upward, strong young men would hold it in place with ropes whilst other team members lit candles affixed all round the balloon. Next, as the ropes were paid out, another stage was attached to this spectacular but impossibly hazardous flying machine, using the same process. Finally - assuming spontaneous combustion had not yet destroyed the floating fairy castle - a third storey was attached, and the fire balloon released to sail majestically into the clouds, thousands of feet above.

That, at least, was the theory. In practice only two, perhaps, in five, of the leviathans got off the ground. Fire was everywhere, with minor injury endemic and, apparently, accepted. Most of those that made it to lift off disappeared over the horizon, doubtless to wreak havoc on some unsuspecting village or cornfield. Three fell on the town itself, the most spectacular of which resulted in the destruction of around one-third of Taunggyi's busy market area. Nobody seemed very much to care. In Shan, it was a case of bo pen yang; in Burmese, nay bah zay. Never mind, don't worry - if that's what it takes to float away sins, so be it. Besides, with the assistance of copious quantities of Mandalay Rum and Padaung Whisky, a good time was had by all.

Text by Andrew Forbes; Photos by David Henley & Pictures From History - © CPA Media