Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Features

Features > STUPA PILGRIMAGE, THAI-STYLE

STUPA PILGRIMAGE, THAI-STYLE

Story by Joe Cummings / CPA Media (25 July, 2020)

Outside Bangkok, a widespread pilgrimage route links a dozen stupas (phra that in Thai), each associated with a different animal in the sip-song rasee, the 12-year astrological cycle shared by most Tai and Chinese cultures. Many Thais believe it is important that they visit the temple associated with their birth sign at least once in their lives, or better yet, on the anniversary of each 12-year cycle (at age 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96 and so on).

Stupas represent both a commemoration of the Lord Buddha's life and the encapsulation of his teachings. According to the Thupavamsa (Stupa Chronicle), King Ajatasattu of Magadha and a Brahmin priest named Drona took custody of the Buddha's remains after his cremation circa 543 BC. The relics, according to legend, were divided into eight equal portions to be enshrined in stupas in eight different locations in what are today northern India and southern Nepal. The verifiable history of the Buddhist stupa commenced during the reign of King Ashoka (circa 269-232 BC), the greatest monarch of northern India's Maurya dynasty and the first Buddhist king in recorded history.

The Buddhist stupa may be the most potent single artistic symbol linking the cultures of the Mekong Basin. An explicit regional representation of Mount Meru, the mythical mountain sitting at the centre of the Hindu-Buddhist cosmological universe, these tapering towers can be found in virtually every corner of the Mekong region. Some stupas, such as the great stupa at Wat Arun in Bangkok or the zedi at Ananda Pahto in Bagan, were consciously designed to imitate the Meru model, with a tall central stupa surrounded by four satellite stupas. Many others, such as the more vertical tap of Vietnam, are much more abstract representations. Originally hailing from India, these marvels of brick, stone or wood proved so compelling that their construction eventually spread to East Asia and beyond.

Legend says that King Ashoka had the eight original reliquaries unsealed so that he could subdivide the contents and inter the relics in 84,000 stupas (to honour the 84,000 discrete constituents of dharma (dhamma) throughout South and Southeast Asia. Although this number may be apocryphal, Thailand's 12 most sacred stupas ultimately owe their inspiration to King Ashoka's historic stupa-building era.

The stupas that cover the 12 animal cycles are found at the following temples:

Wat Phra That Si Chom Thong (Chiang Mai Province) — Year of the Rat

Wat Phra That Lampang Luang (Lampang Province) — Year of the Ox

Wat Phra That Cho Hae (Phrae Province) — Year of the Tiger

Wat Phra That Chae Haeng (Nan Province) — Year of the Rabbit

Wat Phra Singh (Chiang Mai Province) — Year of the Dragon

Wat Photaram Mahaviharn (Wat Jet Yot, Chiang Mai Province) — Year of the Snake

Wat Phra Borommathat (Tak Province) — Year of the Horse

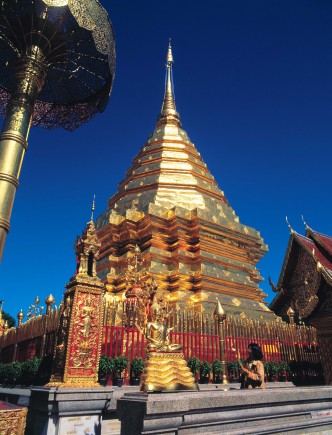

Wat Phra That Doi Suthep (Chiang Mai Province) — Year of the Goat (or Ram)

Wat Phra That Phanom (Nakhon Phanom Province) — Year of the Monkey

Wat Phra That Hariphunchai (Lamphun Province) — Year of the Rooster

Wat Kedkaram (Chiang Mai Province) — Year of the Dog

Wat Phra That Doi Tung (Chiang Rai Province) — Year of the Pig

When paying homage to a stupa, the usual custom is to carry three sticks of incense, a candle and a lotus bud between one's palms — held in front of the chest in a wai or prayer-like gesture – while walking three times around the stupa, in a clockwise direction. When the three-fold circumambulation is complete, the supplicant kneels before one of the altars near the base of the stupa, lights the incense sticks and places them in a receptacle filled with sand. The supplicant then lights the candle and places it atop an iron candle rail, and places the lotus bud on a tray provided for the purpose. A variety of Buddhist verses may be silently recited during this devotional ceremony.

Intention is a key component of all merit-making. Typically one dedicates the merit to loved ones or to humanity at large. To the degree to which such actions are performed for purely selfish reasons, the merit accumulated will be correspondingly less. Venerable Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906-93), one of the most influential Thai monks of recent times, advised against the distractions of ceremonies devised purely for accruing merit. In his landmark Handbook for Humankind, Buddhadasa Bhikkhu states, “If man could eliminate suffering by making offerings, paying homage and praying, there would be no suffering left in the world because anyone can pay homage and pray. But since people continue to suffer despite the various acts of obeisance, homage and rites, it is clearly not the way to liberation.”

THE AUTHOR

Joe Cummings began travelling in Southeast Asia shortly after finishing university, serving as a Peace Corps volunteer at King Mongkut's Institute of Technology in Thailand, followed by stints as an English lecturer in Malaysia and Taiwan. Joe later earned a master's degree in Thai language and Asian art history from the University of California at Berkeley, and was a scholar in residence at the East-West Center in Hawaii. Joe has contributed to over 50 guidebooks, illustrated reference books, atlases, phrasebooks and cookbooks, including his bestselling Lonely Planet Thailand and Sacred Tattoos of Thailand. He is also a regular contributor to periodicals such as the International Herald Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Conde Nast Traveler and Wall Street Journal. Joe has twice been honoured with the Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Gold Award for his work on Thailand. In 2002 he earned the Peace Corps Best Travel Writing award, as well as Mexico's Pluma de Plata (Silver Quill) award for outstanding foreign journalism on Mexico.