Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Archives

Archives > INDIA > Khajuraho

Khajuraho

Khajuraho: A Celebration Of Cosmic Union

SEE RELATED IMAGES @ PICTURES FROM HISTORY

In 1839 Captain T.S. Burt of the Royal Bengal Engineers published in the pages of the prestigious Journal of the Asiatic Society an account of his discovery of an overgrown and abandoned Hindu temple complex in central India. The good captain, writing in the restrained style of the early Victorian era, noted that:

"I found in the ruins of Khajrao seven large diwallas, or Hindoo temples, most beautifully and exquisitely carved as to workmanship, but the sculptor had at times allowed his subject to grow rather warmer than there was any absolute necessity for his doing; indeed, some of the sculptures here were extremely indecent and offensive..."

The carvings Captain Burt had discovered, we now know, formed but a part of an epic story set in stone at the order of the Chandella Kings of central India during the 10th and 11th centuries AD. The Chandellas, scions of a powerful Rajput clan who claimed the moon as their direct ancestor, were devout Hindus who, over a brief period of about one hundred years, built a total of 85 temples to the glory of God, the creation, and the Hindu pantheon.

Eclipsed by the Mughal conquest, the rise of rival dynasties, and the passage of time, the temples languished in the harsh sun and monsoon rains of central India, gradually becoming lost in the jungle. At the time of their re-discovery in 1839, they were so completely overgrown that Burt thought no more than seven temples had survived. Happily this proved far from the case, for when the undergrowth was hacked back and the complex restored, no fewer than twenty two of the original structures were revealed standing.

Each of these temples was found to be distinct in plan and design, yet all shared several common features characteristic of contemporaneous central Indian Hindu architecture. All are raised on high stone platforms several metres off the ground, and comprise an entrance porch, main hall or mandap, and inner sanctum or garbha griha. Perhaps most distinctive are the roofs. Porch and hall are covered by pyramidal structures made up of several horizontal layers; whilst the sanctum is protected by a massive conical tower sometimes 30 metres in height.

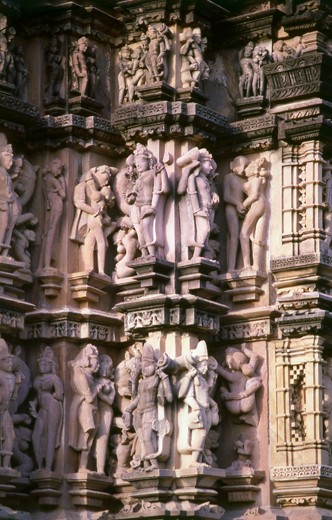

On closer inspection, these structures are made up of a collection of miniature towers or shikhara, each of which is replete with fine, carved detail. Indeed so prolific is the carving on the temples that scarcely a square inch of the external walls remains untouched. From the basement mouldings to the peaks of the shikhara, each building is covered with a mass of lattice work, abstract design and – figurative carvings.

The standard of artistic workmanship is fine and often quite exquisite; but it is the sensual nature of many of the carvings which outraged poor Captain Burt and which has continued to shock, charm and titillate generations of later visitors. The achievement of Khajuraho may be the sum of many parts, but the best-known of those components, and that which has made the temple complex internationally famous, is divine, human (and sometimes animal) sexuality.

Quite simply, the erotic carvings of Khajuraho are a celebration of the sexual aspect of creation set in stone. Stone figures of apsaras, or heavenly maidens, appear in friezes on every temple – a characteristic shared with such Southeast Asian manifestations of Hindu religion as Angkor in Cambodia and the Cham towers of Vietnam. But the apsaras of Khajuraho are distinctly and unmistakably Indian – heavy breasted and broad-hipped, they pout and pose for the tourist camera for all the world like Bombay starlets.

Interspersed between these celestial nymphs are mithuna panels of intertwined couples, triples and larger groups of lovers, some in passionate embrace, others shyly – or slyly – playing the role of voyeur, knowing smiles hidden behind raised hands. One can almost hear the sighs and giggles as they echo down the centuries.

Since Captain Burt's visit more than a century and a half ago, Khajuraho has been well and truly "discovered" and now features prominently on India's tourist map. In recent years the Indian Tourist Board has been promoting the village as an ideal honeymoon destination – already amorous Indian couples, walking daringly hand-in-hand, have become as numerous on temple sightseeing trips as foreign tourists.

Khajuraho can be reached by air – it has its own small airport with daily flights from Delhi, Agra, Varanasi and Bombay – or by train from Delhi to Jhansi, followed by a three-hour taxi ride from Jhansi station. The best time to visit is between October and March, when the weather is mercifully cool, the lawns around the temples pleasingly green, and the clear blue skies offset the ochre shikhara to perfection. Every March, too, an annual dance festival featuring the best of India's classical performers is held on the platform of the Kandariya Mahadev Temple – a time of magic.

For convenience of viewing, the Khajuraho temples may best be divided into two main groups, one to the west of the archaeological museum, and the other to the east. The Western group, in the vicinity of Shiv Sagar Lake, is entirely Hindu and boasts some of the best examples of Chandella art.

Monuments here include the Lakshmana Temple, raised on a frieze of elephants and horsemen in procession. The building faces east, and a steep flight of stairs leads up to the inner sanctum raised high above ground level. Placed still higher is an alcove containing a large image of Vishnu, the creator, with three heads representing different incarnations. Carvings include various deities and celestial beings, including the guardians of the four cardinal points.

On the southern side of the temple are mithuna friezes of an explicitly erotic nature. To the west may be found two exquisitely carved figures which have achieved well-deserved international fame – one of a woman bathing, the other of a woman inspecting the sole of her foot, perhaps in search of a thorn. The women are uniformly voluptuous, clad in little or no clothing, but bedecked with ornate jewellery from top – often literally – to toe.

Close by stands the Kandariya Mahadev Temple. Like all the other buildings at Khajuraho, this structure is built of sandstone, constructed entirely without use of cement or mortar. Dedicated to the God Shiva, there is a ritual linga at the centre of the inner sanctum. This holy-of-holies is reached by way of a flight of stairs leading to the main platform.

There are friezes and carvings everywhere depicting elephants, horsemen, scenes from everyday life, and of course voluptuous, curvaceous Chandella women – or perhaps Chandella men's ideal thereof! Besides large-scale erotic panels which "read" like an illustrated Kama Sutra, there are fine carvings of women playing ball, writing letters, applying make-up, playing musical instruments and generally going about those activities associated with the 10th century Chandella court.

Other fascinating aspects of the rich and varied western group include the Varaha Mandap, with its gigantic image of a standing Varaha, the boar incarnation of Vishnu which saved the world from the primeval flood. The entire body of the boar is covered with carvings of more than six hundred divinities from the Hindu pantheon.

This mighty figure contrasts pleasingly with the nearby Nandi Mandap, dedicated to the bull servant, companion and mount of Shiva. Within the open mandap, under a simple pyramid-shaped roof, stands a large stone image of Nandi gazing with devotion at the Vishvanatha Temple, dedicated to his master Shiva, which rises before him.

The Nandi Mandap, raised high above the surrounding plains, is a fine place to pause for a break and view the whole western group of temples, the streets of Khajuraho village, and the distant Dantla Hills set in the background, before turning to the eastern group of temples a little over one-and-a-half kilometres away. En route it is possible – indeed advisable – to stop for a cold drink and other refreshments near the archaeological museum. After all, getting to Khajuraho takes time, and once there the experience should be savoured and enjoyed – this is not a site to rush through.

The eastern group differs from the temples to the west in that they are mixed Hindu and Jain, and some of the Jain temples are still in active use. Still, the structure and purpose of the religious buildings remains essentially unchanged. The Parshavanatha Temple is a Jain sanctum decorated on its outer sides by two broad bands of sculpture. Here, again, are the many gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon, and a plethora of female forms. Particularly striking images include those of a court lady putting on ankle bells, a woman feeding her baby, and a heavenly nymph applying kohl make up to her eyes.

By contrast, the nearby Adhinatha Temple is an exception to the general rule at Khajuraho. Not that the female form is absent, of course, but here the representations are more lissom and lithe, redolent, perhaps, of the apsaras of Thailand, Cambodia and other parts of Indianised Southeast Asia.

As the sun falls towards the distant, dusty hills, the weary but fascinated traveller may justifiably pause to wonder, what is Khajuraho all about? In fact, it is a single story of celestial love, marriage and creation recounted in stone. Many of the varied and wonderful sculptures are variations on a theme, and that theme is the divine union of Shiva and Parvati. The friezes and panels of the temple complex recount at length and in detail the events surrounding this celestial marriage.

In a poem set in ochre sandstone we see the heavenly guests who attend the wedding, the wonder and delight of the court ladies who break off from their daily chores – bathing, getting dressed, applying make-up, feeding babies – to watch the divine procession go past. Finally, the consummation of the cosmic union of Shiva and Parvati is graphically portrayed time and again in the erotic panels and carvings so characteristic of, and unique to, the magnificent temples of Khajuraho.

SEE MORE KHAJURAHO IMAGES @ PICTURES FROM HISTORY

Text by Andrew Forbes; Photos by David Henley & Pictures From History - © CPA Media