Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Features

Features > Ordaining Pol Pot

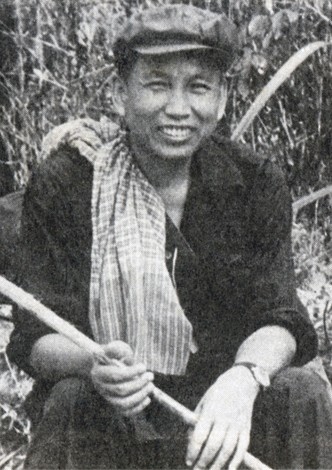

Ordaining Pol Pot

Should Pol Pot Be Allowed Into Monkhood

The Venerable Maha Ghosananda, one of Cambodia's most senior and respected religious figures, recently suggested that both Pol Pot, Khmer Rouge "Brother No. 1", and his most effective and ruthless military commander, Ta Mok, should abandon their struggle and enter the monkhood. "If they agree to be monks, they will give up their ambition, violence and killing," argued Maha Ghosananda in a recent issue of the Khmer-language paper Liberty News.

Maha Ghosananda's suggestion probably springs from a proposal by King Norodom Sihanouk, who indicated the Cambodian government's willingness to accept all Khmer Rouge deserters back into the national fold "Except Pol Pot and Ta Mok. These gentlemen we ask to stay away." The respected monk, appropriately seeking a middle path, argues that ordination of Pol Pot and Ta Mok would at least permit the feared duo to live out the remains of their lives on Cambodian soil.

Hardly surprisingly, perhaps, there has been no official response from the Khmer Rouge leadership. But putting aside the unlikely – albeit intriguing – image of a shaven-headed, saffron-robed Pol Pot making his early morning rounds of Phnom Penh, the Venerable Maha Ghosananda's proposal provides a suitable opportunity to consider Khmer Rouge policies and attitudes towards Buddhism.

In traditional terms, Cambodia was once considered the "most Buddhist country in Southeast Asia". To be a Khmer meant being a Buddhist. The three jewels – Buddha, Sangha, Dhamma – were everywhere honoured, if not always followed, and the national religion was omnipresent. From the smallest up-country village to the heart of Phnom Penh, the country was studded with Theravada Buddhist temples and stupas. Everywhere, too, were spirit houses – those less orthodox but enduringly popular ancillary manifestations of Southeast Asian Buddhism.

Before the Khmer Rouge seizure of power in 1975, Cambodia had almost 3,000 registered temples, and most Khmer men became monks for at least some part of their lives. For example, in the mid-1930s the young Pol Pot spent several months as a novice at Vat Botum Vaddei, a monastery near the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh. Buddhism provided a spiritual explanation for existence, a moral code for living, and a retreat from mundane concerns when this proved necessary or desirable. Disgraced politicians, or those who had fallen from power, often took refuge in the saffron robe – hence, of course, the Venerable Maha Ghosananda's recent suggestion to Pol Pot and Ta Mok.

All this changed with astonishing swiftness after the Khmer Rouge seizure of power in 1975. In the new society Democratic Kampuchea [DK] was building, there was no room for any spiritual or moral authority other than the party. Angkar – the organisation – would brook no rival in its bid to establish total control over the hearts and minds of the Cambodian people, and this alone was enough to seal the fate of Buddhism in Democratic Kampuchea.

Yet issues of control aside, there were ideological reasons why the Khmer Rouge leadership was determined to stamp out Buddhism. The driving force behind intellectuals in the DK leadership – people like Pol Pot and Ieng Sary – was nothing less than the complete transformation of Cambodian society. This goal was to be achieved by blending elements of China's Cultural Revolution with North Korea's Juche, or "self reliance", but taking both processes further, and from an exclusively Khmer base.

Pol Pot and his comrades scorned ideas of a simple "great leap forward" and transitional stages to building socialism. Democratic Kampuchea would achieve communism in a single bound, and that bound would be a "super great leap forward", trebling agricultural production at a stroke.

How could monks fit into such a society? Monks were wandering mendicants, begging for their food, and thus permitting others to improve their kamma through the act of giving. Monks were prohibited by dhamma from working in the fields, in case they harmed any living being – even an insect – which might be crushed underfoot. Worse yet – from a Khmer Rouge viewpoint – monks preached the transience of mundane objectives (like tripling the harvest), and held the achievement of nibbana, or self-extinction, as the ultimate purpose of existence.

Clearly these aims and objectives were at a variance with those of DK intellectuals like Pol Pot and DK military commanders like Ta Mok. To the Khmer Rouge, monks were nothing more than worthless parasites who – rather like townspeople, only more so – lived free from the labour of the peasantry, contributing nothing to society other than a negative, non-productive superstition. Quite simply, they had to go.

And go they did. From the Khmer Rouge seizure of power in 1975 – earlier, in those areas under their control during the civil war – Buddhism was proscribed. It wasn't merely discouraged, or even prohibited; it was physically expunged. Temples were closed (and sometimes torn down), whilst resident monks were ordered to take off their robes, don black peasant garb, and go to work in the fields. Those who refused were unceremoniously killed.

Khmer Rouge propaganda and slogans from this period provide a telling record of DK attitudes towards Buddhism and to the Buddhist establishment.

Pol Pot wished to establish a militarised, fiercely nationalistic state, capable of "taking back" the Mekong Delta region from Vietnam, and the Khmer-speaking border regions of Surin and Aranyaprathet from the Thais. Buddhism abhorred violence, therefore: "The Buddhist religion is the cause of our country's weakness."

Pol Pot wished to build a controlled, collectivised society based primarily on agriculture in which everyone worked. Monks were, by definition, forbidden to work in the fields, and so were parasites. Thus: "The monks are bloodsuckers, they oppress the people, they are imperialists." And again: "Begging for charity is an offence to the eye and it also maintains the workers in a downtrodden condition."

Accordingly, ordinary people were absolutely forbidden to support the sangha in the strongest and most sacrilegious of terms: "It is forbidden to give anything to those shaven-arses, it would be pure waste". And again – only more chillingly: "If any worker secretly takes rice to the monks, we shall set him to planting cabbages. If the cabbages are not fully grown in three days, he will dig his own grave."

During just over three years of DK rule, between April 1975, and December, 1978 – that is, the so-called "zero years", the Khmer Rouge set out completely to disestablish Buddhism. Worship, prayer, meditation and religious festivals were forbidden. Buddha figures, scriptures and other holy objects and relics were desecrated by fire, water, or simply by being smashed up. Pali, the theological language of Theravada Buddhism, was proscribed. Most temples were turned into store-houses or factories; some were destroyed, others – notably Wat Eik and Wat Samdach Money – were converted into prison-execution centres. Only symbols of past Khmer greatness, such as Angkor Wat, were actively preserved, though many temple buildings in Phnom Penh and the other main cities survived the DK period in varying states of disrepair.

At the same time, the monkhood was forcibly disbanded and almost completely destroyed. The most prominent, most senior and most popular monks, including the abbots of many temples, were simply taken outside and killed – on occasion the DK cadres responsible for such executions would display the saffron robes of the murdered monk on nearby trees for the people to see. Those monks who refused to defrock and join the peasantry working in the fields were also killed out of hand. Others who agreed to abandon their robes were forced to marry – Angkar needed a growing population to fight the hated Vietnamese, so celibacy ran counter to the interests of the DK revolution.

Before the Khmer Rouge seizure of power, Cambodia supported an estimated sixty thousand Buddhist monks. After forty four months of DK rule, in January, 1979, fewer than one thousand remained alive to return to their former monasteries. The rest had died – many murdered outright by the Khmer Rouge, but still more as an indirect result of DK brutality, through starvation, illness and disease. Only at Wat Ko, the birthplace of Nuon Chea, Pol Pot's shadowy right-hand man and DK's "Brother No. 2", was a monastery permitted to remain open. Here four monks – almost certainly the only functioning monks in Democratic Kampuchea – received alms from Nuon Chea's mother on an almost daily basis. She disapproved of DK anti-clericalism, and clearly wasn't taking any nonsense from her doting son!

The DK authorities targeted other religions beside Buddhism, of course. Christianity, associated in many Khmer minds with the Vietnamese, was widely persecuted, whilst the Phnom Penh cathedral was demolished stone-by stone. The Muslim Chams suffered terribly – worse, perhaps, than any other group. In a disturbing parallel with forcing Buddhist monks to marry, Cham Muslims were often obliged to keep pigs and sometimes to eat pork.

Belief in locality spirits, or Neak Ta, widespread throughout Cambodia, was also condemned by the DK – though in a somewhat circuitous way, according to some informants. Perhaps because so many of the DK "base people" – the poor peasants and hill-tribe minorities who made up the core of Khmer Rouge fighters during the revolution – believed in these spirits, a different approach was sometimes adopted.

Instead of denying the existence of Neak Ta outright, the Khmer Rouge would sometimes just shoot up the spirit houses to prove their superior power. According to one thirty-two year old Khmer Rouge veteran interviewed in 1976: "Even the Neak Ta were afraid [of the Khmer Rouge], and didn't dare act up against them".

With the destruction of the Democratic Kampuchean regime and the expulsion of the Khmer Rouge from Phnom Penh in 1978, a concerted and increasingly successful attempt has been made by the new Cambodian authorities to restore the national culture. At the forefront of this movement has been the return of organised religion. Monasteries were re-opened, prohibitions on making offerings and holding festivals have been lifted, and Cambodian Buddhism is gradually recovering from the Khmer Rouge onslaught. Islam, and Christianity, too, are making similar comebacks.

One sign of the success of the restoration of Cambodian Buddhism is undoubtedly the Venerable Maha Ghosananda's suggestion that Saloth Sar [alias Pol Pot], and his redoubtable military lieutenant, Chhit Chhoeun [alias Ta Mok] should join the monkhood.

This neat and very Cambodian solution to the continuing problem of Khmer Rouge insurgency would likely prove equally unacceptable both to Prime Minister Hun Sen, and to the Khmer Rouge leaders themselves, however. More probably, both Pol Pot and Ta Mok will choose to remain outside the monastery and in the jungle.

One can only speculate, but perhaps the temple murals and Buddhist scriptures relating to the eight hells reserved for special sinners might prove too uncomfortable for their contemplation.

Text by Andrew Forbes, photos by Pictures From History – © CPA Media – October 1995